One of my favorite manga at the moment is The Summer Hikaru Died, which is (broadly) about an Eldritch Horror that comes down from the mountains in Japan and takes over the body of a dead high school boy. It experiences ice cream and friendship and heartache and tries to wrap its mind around why killing people is wrong.

In a recent interview, the writer of the story, Mokumokuren, talked about how they approached writing it. “Ever since I was a child,” they said, “I’ve always found myself empathizing with the monsters in stories.” They talk about how disappointing it was that the Beast from Beauty and the Beast turned into a handsome man at the end, rather than being a monster wholly and fully, and the manga itself examines the idea of how monsters and humans interact.

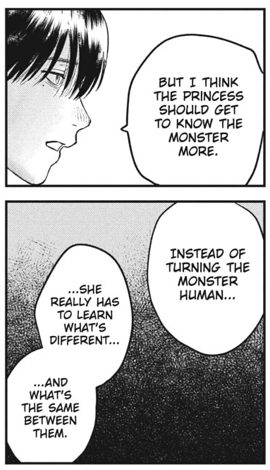

There’s even a bonus section where the Eldritch Horror and the Boy Who Loves Him are reading a storybook, and the latter says, “I think the princess should get to know the monster more. Instead of turning the monster human, she really has to learn what’s different and what’s the same between them.”

This is, of course, a major theme of the manga. But, given our exploration of monsters over the last fifty or so entries, I thought it was something we could turn around in our minds as well.

After 49 monsters, you know how this all usually works. We look at a stat block, investigate the lore, see what the writers at Wizards have come up with over the last fifty years and what fans have developed on their own. A little combat, a little world-building, some poking at the symbolic resonance of the creature and we’re done, right?

But maybe – just maybe – it’s time to consider a very important question:

Who chooses to see something as a monster?

At a D&D table, there are basically three forces at play who determine what makes a monster. Let’s look at them one at a time.

The first Monster Maker — and maybe the most influential — is Wizards of the Coast. They make a whole Manual for them, for Mystra’s sake! If a creature gets a stat block, it’s fair game. That’s why the Monster Manual gives us AC and HP, not star signs, turn-offs, or favorite foods.

The authorial intent from Wizards is clear: If it bleeds, it can be killed. If it’s in the book, it probably will be.

This is, of course, perfectly fitting for a game that evolved from battle simulations. D&D is, at its core, a combat engine, with story and social play built around it. The game encourages violent solutions to problems, and, what’s more, expects them. Strahd can’t be talked down from his villainous perch in Ravenloft. Tiamat won’t be wined and dined into leaving the Material Plane alone. Vecna doesn’t negotiate.

These aren’t failures of imagination — they’re design choices. These options aren’t written into the stories because the writers at Wizards don’t want them there.

And I want to be clear here: there is nothing wrong with this. Heroic stories, from the earliest myths onward, have been about heroes fighting monsters, not making friends with them. Wizards is following well-worn tracks of heroic storytelling, and has given us hundreds of monsters to use for any occasion.

It does raise the question, though, of whether this expectation for violent solutions to problems is placing limitations on our game tables. By choosing to play D&D, you are choosing violence as an option, either consciously or unconsciously.

Even so, Wizards has made some great strides over the years in how they determine what is or isn’t a monster. For example, the 2014 Monster Manual tagged entire species as “essentially evil.”

Drow: Neutral Evil. Orcs: Chaotic Evil. Kobolds: Lawful Evil.

No exceptions. No nuance.

But in the 2024 update, that’s changed. Wizards moved away from Essential Alignments, especially for Humanoids, which is a strong statement by them about what it means to be a monster. Drow, Orcs, Kobolds, Goblins, Gith – creatures which would have once been default enemies are now officially allowed to be people, good or evil on their own terms.

But why stop there? Why should only the humanoids be spared? Why not the Dragons? The Aberrations? The Undead? Why must all Beholders be Lawful Evil and all Gold Dragons Lawful Good? Why can’t we treat individual Vampires and Hags and Cultists as people rather than just assuming that they have evil intent?

Well, we can. And that’s where our second Monster Maker comes in: The Dungeon Master.

One of the keystones of D&D is that the real game happens at the table, not on the printed page. Wizards knows this. Once the book hits the table, it’s out of their hands, and rightly so.

The Dungeon Master takes what Wizards provides and turns it into something alive. Whether they’re playing a published adventure module or making up their own world, they still have the final choice of what monsters appear.

You enter a forest clearing, sun-dappled and quiet. The birds have gone silent. Something rustles in the underbrush. Out steps a…

What is it?

A cute little deer, just minding its business?

A lurching horde of undead?

Volo?!

That choice matters, and the DM’s framing of that choice matters. If the lurching undead offer your party a bouquet of flowers and an invitation to the Fresh Start Club for recovering post-living individuals (should the worst come to pass), what happens then?

Maybe that adorable little deer is the host organism for the Infinite Armies of the Abyss, just waiting to open its too-many eyes.

Maybe Volo is… well, Volo. He’s tough to gauge.

The DM has enormous power to make a monster and countless ways to do it. We can give it sentience, nuance, purpose, or strip it down to pure instinct and violence. We can enmesh it in the machinations of greater powers, have it boldly defy convention, or craft an entire world expressly to justify having happy, jolly Beholders.

When we decide something is deserving of a violent end at our table, that is a choice we make.

Whatever is driving the main conflict of your story, whether it is a monster or a villain, you have created something that won’t play along. Your world has rules, boundaries that define what “good” and “evil” mean in its context.

The monster you put in front of your players either can’t — or won’t — play by those rules. That makes it dangerous. That makes it a monster.

Which brings us to the third and final Monster Maker: The Players.

Every DM knows one thing for sure: nothing in your game is truly real until it hits the table. The characters your players create may grow from your world, but they’re ultimately beyond your control. Nothing will kill a game faster than the DM telling their players, “No, your character wouldn’t react that way.”

Much of the time, your players have joined a game of D&D so they can go monster hunting. If you have a bunch of murderhobos at your table, perhaps that is the only reason they’ve joined. Either way, they’ve signed up to be heroes in your world, and where there is a hero, there must also be a monster.

Players often see monsters (end bosses excluded) as impediments to progress. No one stops to ask why the Duergar are guarding the gate — they just want what’s behind it.

And it makes sense! D&D is a power fantasy. We play this game because we want to be Big Damn Heroes. A D&D game has so many things we can’t have in our own lives: magic, mystery, a band of close friends, clearly-defined career progressions.

And monsters.

Clear-cut, guilt-free, kill-’em-and-move-on monsters. And in most games, your players won’t hesitate to fight their way through them.

But what if they do hesitate?

Much as your world has its rules about what good and evil are, your players will craft their own. Most of the time they’ll play along. If you decide that everything non-human in your world, from Elves to Oozes, is evil, then they’ll probably roll with that. Most players will go with what you put in front of them, kill who you tell them to kill, and do so with a song in their heart.

But that doesn’t mean they have to.

It is within a player’s ability to ask what is maybe the most dangerous question about morality: Why?

Why did we have to kill that band of orcs? Maybe they just resented the incursion of humans into that territory.

Why did we need to kill that dragon? Wasn’t there a better way to deal with a creature that is, after all, intelligent?

Why were we required to kill that vampire? It wasn’t her fault that she was made undead. Maybe, if we’d tried, we could have released her from her curse.

These are all valid questions to ask, and as a DM you should have an answer that’s better than simply, “Because.” But even if you don’t, your players are going to make the final determination of what is and isn’t a monster. Regardless of what Wizards of the Coast publishes, or what the Dungeon Master puts in their lore document, it is the players’ decisions that drive the story forward.

And if they decide the Aboleth under the waves isn’t the real monster? Or that the smiling baron — the one with too many missing children — is?

Then you’re going to have to go with that, and make it make sense.

Wizards of the Coast decides what gets a page. The Dungeon Master decides what gets placed in the world. The players decide what gets killed.

And between those decisions, something amazing takes shape. A shared definition of what it means to be good or evil, and an ongoing argument about what to do with both. Just like the great sagas of old, how we deal with monsters in our games reflects our values. It’s a statement of purpose: this is how evil should be confronted, or how goodness should be protected.

But we must be mindful of our approach. A monster can be more than a stat block.

It can be a story you’ve chosen not to understand. A fear you’ve decided to feed. A shortcut. A scapegoat. A funhouse mirror of yourself that you can’t bear to look at because it reflects things we don’t want to admit about ourselves.

Our violence. Our righteousness. Our need to be in control.

Our excuses.

Because here’s the truth: in our D&D game, as in real life, monsters are only monsters because we need them to be. Because we feel the story doesn’t make sense without them.

Maybe the handsome Eldritch Horror sitting across from you is exactly what you need right now, and accepting it as it is will be a far wiser choice than trying to stab it to death.

We decide who the monsters are, and that is a heavy responsibility for everyone at the table.

So. Here we are at Monster #50. Along the way, you’ve met vanishing dogs, oracular undead, beasts of burden and bearers of blessings.

Now maybe it’s time to ask: What do you call a monster?

And what does that say about you?